|

|

| Over

the last decade Leandro Katz developed two significant bodies of work: The Catherwood Project and Project for the Day You'll Love Me. The Catherwood Project (1985-95) is a photographic reconstruction of the visual documentation of the Maya monuments made famous by the artist Frederick Catherwood in the mid-nineteenth century. The drawings by Catherwood of Maya architecture and sculpture were the first accurate ones ever published. Project for the Day You'll Love Me is part of a larger photography and film project titled El Día Que Me Quieras (1997). The visual point of departure for this ongoing project is Freddy Alborta's mortuary photograph of Ernesto "Che" Guevara that circulated worldwide on October 10, 1967, the day after Guevara's execution. Both projects comment on significant historical moments in Latin America. One of those moments resulted in the combined discoveries of Catherwood and the lawyer -writer John Lloyd Stephens who correctly attributed the great archaeological ruins to the Maya. The other resulted in Che Guevara's demise in the Bolivian highlands, marking an end to a chapter in the region's history of armed struggle. The two projects share common perspectives while addressing different issues, time periods, and historical circumstances. They are visually linked by the use of photography and photographic-based imagery. The result of extensive research, on-site documentation, and actual journeys, the projects retrace the footsteps of historical figures whose legacies are currently under study in the various disciplines of art history, archaeology, political science, history, and journalism. The two projects are contextualized from individually compelling angles in which the camera's lens closes in to provoke a reevaluation of different historical events with resonances relevant to the present. Such historical searches locate Leandro Katz within the broader discourses of contemporary art in his attempt to recapture personal and historical memory as well as to inquire into death and transcendence. |

|

| The Catherwood Project features thirty-seven photographic prints and a photographic installation. When Leandro Katz set off on the trail of Frederick Catherwood, the artist was familiar with Catherwood's drawings of the Maya sites. In photographing the monuments that Catherwood had drawn, Katz attempted to "enter into the vision of Catherwood by looking for his precise point of view that he had used." Katz developed five different approaches in this process of adapting the earlier artist's point of view. The artist positioned himself in situ so that he could capture the view of a given monument from the same angle as Catherwood had. In the process of adapting this new way of seeing, Katz realized that the English artist, using a camera lucida, had successfully rendered the buildings in the distance while at the same time capturing the details near at hand. |

|

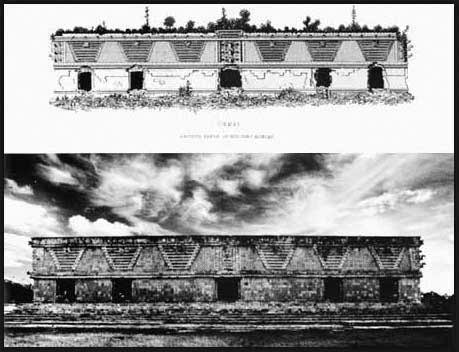

| In order to demonstrate Catherwood's depiction of the near and the far in a single rendering, Katz, in his first approach, juxtaposed his present-day view of the monument with a reproduction of Catherwood's engraving, for example, in House of the Nuns, after Catherwood [Uxmal] of 1985. |

| Another comparative analysis is noted in Uxmal, after Catherwood, 1985, in which Katz juxtaposes his photograph with a photographic reproduction of Catherwood's engraving of the southeast corner of the House of the Nuns, often referred to as Monjas. The engraving reveals the beautiful details of the stone facade which the English artist must have examined closely in order to draw the unfamiliar Maya motifs with extreme accuracy. Such comparisons demonstrate the changes that have occurred to the buildings over time. Many of the details visible to Catherwood have been erased by the wind and the rain, by time and man. |

|

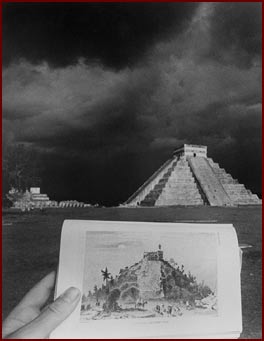

| Leandro Katz's second approach features his view of the monument together with a hand-held book containing the Catherwood engraving of the same monument. Two notable examples are Half Buried Idol, Copán of 1989 and Uxmal -- Casa de las Palomas of 1993. In addition to locating Catherwood's position in order to capture the same viewpoint, and thus present an objective comparison, Katz asserts his subjectivity. By including his hand on the page of the book, he places himself discretely within the frame, becoming a participant on two levels, that of the observer and the observed. While following the rigorous mode of an objective documentarist (as attested to by recovering Catherwood's viewpoint and evolving formats that allows us to compare the two visions), Katz also lets his personal vision to come into play. |

|

| This may be seen in any number of works in which the artist captures the qualities of light during different times of day and the cloud formations in varying climatic conditions. An impending storm sweeping across the sky is presented in El Castillo [Chichén Itzá] of 1985, reminding us of the dramatic meteorological conditions in J.M.W. Turner's work. In Uxmal -- Casa de las Palomas, the monument and the steep foreground before it are enveloped in a play of light and shadow. Different times of day -- dawn and dusk -- are captured respectively in Palace and Tower at Palenque of 1986 and The Palace of Sayil. |

|

|

Katz's third approach excludes the Catherwood's drawings. Although the earlier artist documented the Temple of the Foliated Cross in a schematic line drawing, the nineteenth-century work is not part of Katz's Palenque, the Temple of the Foliated Cross of 1986. While adopting the same frontal viewpoint from which to take the photograph, Katz took a long-distance shot of the building surrounded by the lush, tropical vegetation. In his fourth approach, Katz takes liberties and photographs buildings around those that Catherwood drew without rigidly following the proscribed angle of the English artist. El Castillo [Chichén Itzá], for example, departs from its antecedent, as is noted in the comparison of the engraving in Katz's hand-held book. In works such as El Castillo, desde el Templo de los Guerreros [Chichén Itzá] of 1985, Katz finds his own vantage point from which to photograph El Castillo (The Castle), thereby inserting his subjectivity in a manner distinctive from that of most of the work in the project. The view in the photograph is taken from the Temple of the Warriors near the statuary of the Plumed Serpent looking out toward the Castle. Katz's photograph includes the image of another visitor who is also photographing the ruins. |

|

| There are a number of works, including Temple of the Descending God, Tulum of 1985, that feature the ubiquitous tourists. By incorporating this aspect of the here and now in these historical reconstructions, the artist comments on the transcendence of these monuments over different generations of visitors to the sites. Many of these visitors are profoundly interested in retracing the steps of former investigators who have inspired a fascination with, and a profound respect for, the pre-Columbian monuments. |

|

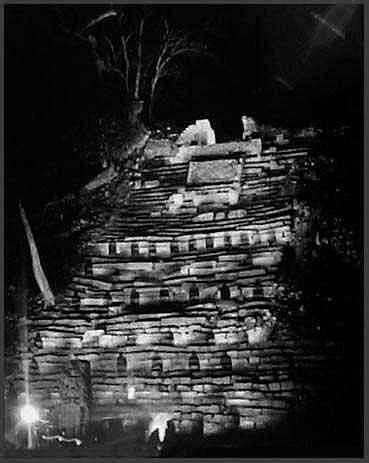

| In the fifth approach to the Catherwood Project, the artist himself enters the frame cloaked in a black photographic cloth. Copán -- Ritual para un Tiempo Transfigurado of 1992, Arco de Labná -- Ritual para un Tiempo Transfigurado, Labná -- Estudio para el Alba del Tiempo Transfigurado, Labná -- Estudio para la Noche del Tiempo Transfigurado, all of 1993, are responses to Catherwood's night scenes. In these works the artist's silhouette casts shadows over the monuments in measured steps. Katz carefully devised a technique that enabled him to use an open flash to light the entire monument over a period of four hours in the pitch black of night. In Copán -- Ritual para un Tiempo Transfigurado, the artist moved six feet each time he fired a flash of light until the monument was photographed. The stunning results feature the repeated image of a shrouded black figure over the stairs of the structure. In the upper left of Arco de Labná -- Ritual para un Tiempo Transfigurado, streaks of light appear, the paths of the stars moving in the sky during the several hours of shooting. Although the ritual performed was a photographic one, it connects symbolically with the Maya monument and evokes associations with ritualistic celebrations that were at the heart of Maya life. |

|

|

| Katz had to devise new techniques to enable him to achieve a deep focus shot (the view of the near and far in a single view) in the manner of Catherwood. In Kabah Interior [after Catherwood] of 1993, the challenge was to capture a sliver of light that comes into the chamber for some fifteen minutes each day and also to illuminate artificially the hand-held book with the engraving. Dentro del Templo de las Máscaras, Kabah of 1993 provides another view of the interior chamber. Once again the artist waited for hours inside the chamber for that brief moment when the sunlight bathes the area in gold. That waiting period had a sense of magic about it: swallows flew overhead, mosquitos buzzed, birds sang. One cannot help but wonder about similar moments of magic that, together with the hardships, have been experienced by Stephens and Catherwood on their long-ago journeys. |

|

|

| The selection of work discussed in this essay is part of the larger work-in-progress Project for the Day You'll Love Me, and the documentary film El Día Que Me Quieras (released in 1997). Project for the Day You'll Love Me consists of seven installations, twentyseven photographic prints, and a chronology in the form of a forty-one foot horizontal scroll. The origin of these works can be traced to events that occurred in the mid-1980s during the civil wars in El Salvador and in Nicaragua. At that time there was a proliferation of journalistic images of death which presented a negative view of Latin Americans mired in violence. With this concern in mind, Katz began a work based upon a series of images of cadavers. The artist appropriated an image, shown on television, of two Salvadoran boys who, with their mother, were searching among dead bodies for their father. In producing a photograph of this image, Katz wrote the caption "First You Kill Our Leaders and Then You Call for Elections." |

| During the conceptualization of this work, the artist recalled the trophy photo of Che Guevara, one of the most daunting images of death. Indeed, to this day, the photo of Che Guevara's body displayed on top of a laundry basin remains embedded in our collective memory as one of the most powerful images to circumscribe the literal exactness of death. |

| Over the next few years, the artist identified and located Freddy Alborta, the photographer in Bolivia who took the picture, and did research on the photo itself and the questions it raised wth respect to the nature of representation. For example, the artist began to focus on small details in the photo and was puzzled by the wet trousers open in the front, by a strange, unidentifiable contraption held by one of the civilians, and by what appeared to be a forearm on the floor. One question led to another, as did each new discovery. As the project evolved, the artist formed an extensive archive containing both visual material and texts. Diverse texts provided the artist with information from which he compiled the Chronology that begins with entries related to the guerrilla movement in Bolivia in May 1963 and ends with events connected to it in the present. The Chronology charts the almost daily incidents in Guevara's final eleven-month campaign in Bolivia from the date of his arrival on November 4, 1966, to his death on October 9, 1967. The remarkably reductive and yet arresting imagery in the seven installations was transformed from small, poorly reproduced images in printed matter into large photographic displays. |

| Although the last photograph of Che Guevara is the core element around which conceptual exploration of the larger project unfolds, it is not, as might be expected, the leitmotif of the installations in the Project for the Day You'll Love Me. Instead Dr. Adolfo Mena González, 12 Guerrilleros, Monika Ertl, and Tania, images of the central protagonists in the Bolivian campaign, form the leitmotif of Project for the Day You'll Love Me. In the Chronology their fictive characters, activities, and captures are chronicled in multiple entries. The subjects featured in the installations, Adolfo Mena González, the twelve guerrilleros, Monika Ertl, and Tania, carried out their clandestine functions in disguise, operating under at least one nom de guerre. In reconstructing the myth and icons of the central events in Guevara's Bolivian campaign, the artist presents images of people whose identities are mercurial and reinvented, deceiving and powerful. When Che Guevara entered Bolivia on November 3, 1966, his Uruguayan passport falsely identified him as Dr. Adolfo Mena González, a functionary of the Organization of American States. Mena González' passport photo featured him clean-shaven and bald-headed. The disguised middle-aged man went through customs virtually undetected. Within three days Che successfully reached Nancahuazú, the center of guerrilla operations where he began to write his famous diary, Diario Boliviano. The striking, iconic images of the 12 Guerrilleros are portraits of men whose noms de guerre were Pedro, Luis, Urbano, Andrés, Ñato, Marcos, Chino, Moro, Pombo, Ricardo, Pacho, and Negro. They were identified in a series of drawings by Ciro Roberto Bustos, who was captured by the Bolivian army following a meeting he had with Che Guevara. During his imprisonment, Bustos was forced to draw the portraits of Che's inner circle. Although he tried to misrepresent their appearance, he finally produced what the military accepted as authentic representations. |

| The Monika Ertl installation features the disguised image of Ertl with a wig and glasses. Other elements include a gun, a written message, and the picture of the dead Roberto "Toto" Quintanilla. The images come from police files in Hamburg. The German-born, Bolivian-raised Ertl joined the E.L.N. (Ejército de Liberación Nacional) under Guevara's sucessor, Inti Peredo, who was killed on November 9, 1969 by the Bolivian Secret Service headed by Quintanilla. In apparent political revenge, Ertl, under the false name of Imilla, allegedly killed Quintanilla in his consular post in Hamburg on April 1, 1971. Monika (Imilla) Ertl was later ordered killed by Klaus Barbie (the "butcher of Lyon") after he learned of her intentions to turn him over to the French police. |

|

| The portraits of Tania feature five images-disguises. At the end of 1964 Tamara Bunke "Tania" arrived in Bolivia, where she operated under a series of assumed names and appearances. She made her way into journalistic, intellectual, and official circles in La Paz, where she began her mission of infiltration. She was, in all likelihood, the person who set up the support contacts for Guevara in La Paz. She was wounded in the ambush of Vado del Yeso (August 31, 1967); her body fell in the water and was found downstream in the Río Grande a week later. |

| The subjects in these installations are the images of fictitious identities. Questions of beguiling identities and mysterious events are also the subjects of the twentyseven photographic prints Project for the Day . . .. In contrast to the dramatically reductive and sober portraits of the installations, the imagery in the photographic prints features objects, images, and fragments from newpaper headlines providing rich, colorful, and multilayered compositions that were constructed in three-dimensional setups for the camera. The depth of field presents the objects in focus and out of focus at the same time. One's eye darts back and forth, connecting the fragmented images to their larger sources. In many of the photographic prints, we find quotations from the photographs of the dead Che Guevara, including fragments of the famous photograph by Freddy Alborta. We also see partial views of such figures as Adolfo Mena González and Tania. Fragments of headlines announce Che's captor and the misleading and conflicting reports surrounding the circumstances of his death and burial. More gruesome yet, one of the headlines announces that Che's hands were sent back to his widow. In two prints the image of Rembrandt's The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp and Mantegna's Dead Christ are juxtaposed against fragments of the Guevara photo, thus recalling John Berger's analogy of the three images. Finally, as if in a slow dance, the letters spelling the Spanish title of this project, El Día que Me Quieras, move across the surface. In appropriating the title of the famous tango "The Day You'll Love Me," the artist brilliantly simulates through the imagery the point and counterpoint of that melodious dance replete with its tense, emotional associations. Julia P. Herzberg © 1995 |

| First published

in the exhibition catalogue Leandro Katz: Two Projects/A Decade El Museo del Barrio - New York |

Photo Projects | Installations | Mural Texts | Books / Catalogues | Film / Video | Contacts •Español | •English | Home |